After cycling to Mirambeau, on to Royan and back down to Saint-Seurin-de-Cadourne, it was on to our home straight, although the first stop on this, our final day, meant a short eastward detour via Saint Germain d'Esteuil to pay a visit to the Domaine de Brion where ruins of Gallo-Roman-era edifices – a theatre, dwellings and a temple – sit silently in amongst the trees and marshland pastures.

Back in the 1st century AD, this area was still an island, rising above the surrounded waters which have subsided and been irrigated over time. In all likelihood, a whole settlement spread in all directions, and the eminent 19th-century archaeologist

Léo Drouyn believed that the area may have been known as Noviomagus, as referred to in Claudius Ptolemy’s Geography, which around 150 AD exhaustively compiled all geographical knowledge of the 2nd-century Roman Empire.

We started out by inspecting the remains of the theatre, which expert estimates suggest could have stretched to a diameter of around 55 metres and held around 2,500 spectators. This is difficult to believe when looking at the isolated sections which have somehow survived all these years, but still we enjoyed picturing the scene, imagining spectators streaming through the archways and up into the stands. To one side stood a more angular formation, which is what remains of a second-generation construction, a medieval-period tower inhabited by a knight who had been banished to the area after seeking to exact money from locals. The tower had been built from stone used for the theatre!

|

| The remains of the theatre. |

Advancing a little further into the wild, we viewed what is little more than the foundation structure of two homes, which are resolutely facing the same direction, suggesting some form of urban planning which may arguably have been applied to other Noviomagus buildings. Indeed, also facing the same direction is what remains of a full-on temple, which was reportedly destroyed by fire in the 3rd century and pillaged over subsequent years. Digs carried out in 1989 and 1991 unearthed a significant number of objects, including a number of bronze statuettes that paid homage to Gallo-Roman pagan gods.

|

| Gallo-Roman housing. |

|

| Inspecting the temple. |

So why did this hive of activity fade into nothingness? That is a question for historians to deal with but, if our experience is anything to go by, we had to make our time on site as short as was humanly possible because, given the moist environment, we had to contend with the most humongous, aggressive and hungry mosquitoes we think we’ve ever encountered. It became so unbearable that we barely had the time to read the faded information panels, let alone explore the ruins for ourselves. Did flying insects bring down the Roman Empire’s presence in the Médoc then? Whatever, this little-known place deserves greater exposure, something that local authorities are unable to adequately fund at the time of writing.

Using the nearby north-south railway line as our guide, we glided fairly effortlessly to our next port of call, the picturesque, semi-perched village of Vertheuil. As peaceful as it was on this springtime Saturday mid-morning, it had clearly geared itself up for its steady trickle of visitors passing through, with a series of ten information panels dotted around the centre, providing stories of bygone times and archive yesteryear photos of the village as it used to be. The small-scale heritage trail, known as

Le Musée dans la Rue (museum in the streets), takes in predictable sights such as the war memorial, a small fortified castle, the village hall, the church and its neighbouring abbey. But it also taps into some of the fixtures of village life including the bakery, hairdressers and butchers. It is a fine initiative that makes grassroots history instantly accessible to tourists.

|

| Vertheuil fortifications. |

We were then magnetically drawn to the largest community in that central Médoc area, the town of Saint-Laurent-Médoc. There was more life about the place there than anywhere we had encountered since Soulac-sur-Mer. Despite being located some 45 kilometres to the north of Bordeaux, the town is now viewed by many as being inside the city’s commuter belt. But while we were tucking into locally-purchased food sat on a bench on the church square, we spotted a coach service to Bordeaux picking up passengers. Watching people saying their goodbyes, the city still felt a long way away. Just as we were about to leave Saint-Laurent, we stopped outside a café and were about to set up shop on the establishment’s terrace with a view to enjoying a pick-me-up combination of coffee and soft drinks. The café staff turned us away, claiming the late-lunchtime hour meant the place was now out-of-bounds for patrons. Feeling simultaneously thirsty, rejected and ever so slightly dejected, we got back on our bikes.

The most logical route hereon would have meant cycling along the hard shoulder of a busy dual carriageway, so we instead looped around to the hamlet of Benon where, to our immense surprise, in the leafy environment niched in behind a fairly anonymous housing estate lay a remarkable 12th-century country church, Eglise Notre-Dame de Benon. We ventured inside and enjoyed the respite delivered by the cool air there, before trying to make sense of one of the wordiest, most incomprehensible memorials I think anyone has ever positioned anywhere in the world. It appeared to commemorate a service held there in remembrance of a Maltese dignitary who died in a plane crash nearby in 1991. The story certainly appeared to merit further research, but we were all so exhausted from just trying to read the panel that we were reluctant to take things to the next level. We went back outside and instead admired the three church bells visible up high, and which alone provide an instant journey through time, cast as they were in 1776, 1873 and 1886. The eldest (and smallest) of the three bells is even listed as an historic monument.

|

| And the Invisible Bordeaux award for the most incomprehensible plaque EVER goes to... |

The linear route then took us through another mid-sized town, Castelnau-de-Médoc (where we were at last able to buy in some drinks!), and on to our final brief stop, outside

Saint-Raphaël chapel. This tiny place of worship was built here around the late 15th century on the spot that, in 1375, saw the birth of one Pey Berland to a father who was a labourer from nearby Avensan and a mother who was a peasant from Moulis. In spite of these humble roots, Berland was educated by a local notary before being sent to a clerical school in Bordeaux after the death of his father, then to university in Toulouse. Returning to Bordeaux, he became a priest in Bouliac to the south-east of the city around 1412. He went on to become secretary to the Archbishop of Bordeaux, travelling around France, Italy and England in this capacity, before Pope Martin V appointed him Archbishop of Bordeaux on August 13th 1430.

Pey Berland subsequently went on to become one of the most influential of all figures in medieval Bordeaux, and much of what he instigated (at a time when the city was in profound moral and economic turmoil) continues to live on today. The aptly-named Tour Pey-Berland, the cathedral’s bell tower, the construction of which began under his authority in 1440 (it was completed in 1500), is the lasting landmark which is most naturally associated with him, but he is also responsible for the founding of the original University of Bordeaux (in 1441), Saint-André hospital and a number of secondary schools. Pey Berland, we therefore salute you, as does the virgin mother and child statue positioned at the very top of Tour Pey-Berland, which symbolically faces in the direction of Saint-Raphaël.

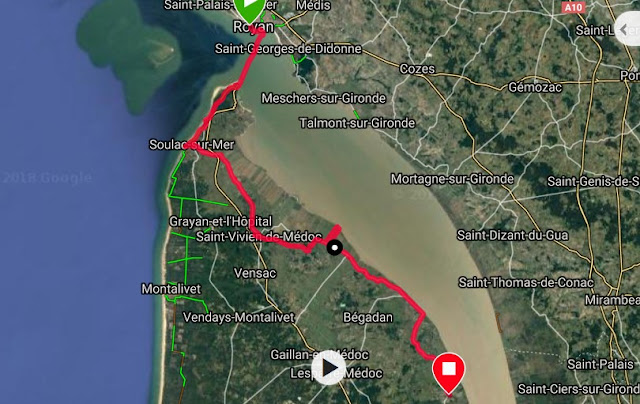

By now we were barely ten kilometres from our Saint-Aubin-de-Médoc basecamp. Four days of virtually continuous cycling had taken their toll and our average speed over the final stretch was certainly nothing to get overly excited about, but there was a definite sense of job very much done as we turned back into our street. Via Margaux, Lamarque, Blaye, Mirambeau, Talmont-sur-Gironde, Saint-Georges-de-Didonne, Royan, Le Verdon-sur-Mer, Soulac-sur-Mer, Jau-Dignac-et-Loirac, Saint-Seurin-de-Cadourne, Vertheuil, Saint-Laurent-Médoc, Castelnau-de-Médoc and many more places in-between, we had cycled all the way up one bank of the Gironde estuary and back down the other, and life on the saddle of a bicycle doesn’t get much better than that.

|

| Gironde Estuary cycle tour day 4 mapped out. |

And, in case you missed them, here is where you can rewind to day 1, day 2 and day 3 of the Gironde estuary cycle tour!

5 commentaires: