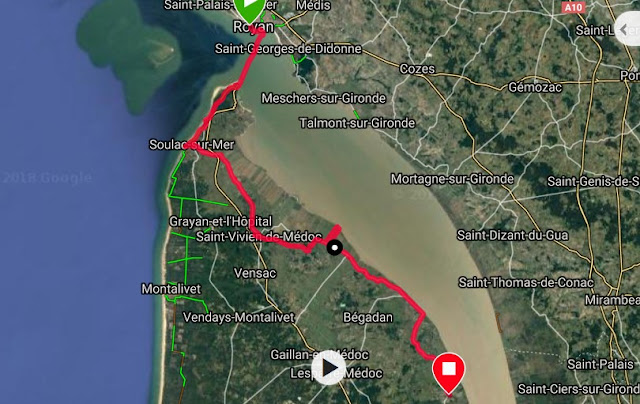

Having cycled from Bordeaux to Mirambeau and on to Royan, here we are on day three of a tour of the Gironde estuary, which started off with us following signposts to the ferry port in Royan so we could cross back over to the left bank of the estuary.

En route we engineered a short detour to view our second Operation Frankton memorial. This one was formed by a flower-like arrangement of five canoe-shaped “petals”, four of which are made of see-through blue Perspex. Behind the various shades of blue lay the spot in the distance where the Marines exited the submarine that had brought them from the UK to south-western France on this daring mission.

The ferry we caught, L’Estuaire, was a wider, longer and generally meatier affair than its Lamarque-Blaye counterpart further upstream, built to carry up to 600 passengers and 138 cars (whereas the Sébastien-Vauban caters for a lowly 300 passengers and 40 cars). After a 20-minute voyage we were back on dry land and cycling the short distance towards the very northern tip of la Gironde, la Pointe de Grave, to inspect the three memorials that I had last viewed during my Girondin four corners road trip: one saluting General Pershing’s First World War US troops who had defended France, another generally commemorating all those who gave their lives in the fight for the freedom of France during the Second World War, and the third completing our trilogy of Gironde estuary Operation Frankton memorials. This one comprises four separate leaning stone panels, providing a full historical overview of the raid, an illustration depicting the mission in progress, and a host of military insignia.

We had our own leisurely mission to accomplish, so we picked up the southbound cycle path running alongside a disused railway track parallel to the Atlantic coastline, which took us all the way into the pleasant northern Médocain seaside resort of Soulac-sur-Mer. Our first port of call was one of the world’s many replicas of the Statue of Liberty, symbolically positioned on the seafront looking out towards the United States. An explanatory text at the base of the statue explains that it was commissioned by the town in 1980 and manufactured by the Paris ateliers of Arthus-Bertrand, using the original mould designed by sculptor Auguste Bartholdi. However, an urban legend also suggests that the statue is the very one which was located on Place Picard in Bordeaux from 1888 until its disappearance at the hands of the Germans in 1941. Which version is true? Most probably the former…

We were then naturally drawn towards le Signal, an angular apartment block which has long been an eyesore for some, but was a much-loved home and holiday residence for others and was initially set to be just the first of a number of such buildings in Soulac. Importantly, when it was built, between 1965 and 1970, the ocean was a good 200 metres away. But over the ensuing years, the Atlantic has literally gained ground on this lone building, at a rate of between four and eight metres per year.

Le Signal therefore now perches precariously at the water’s edge, and after the violent winds and harsh tides of early 2014, the Atlantic was officially declared the winner and residents were hurriedly evicted from the premises. Since then, the residence has fallen into a state of disrepair, becoming a haunt for squatters, looters and vandals, and the co-owners – some of whom are still paying off the mortgages which enabled them to acquire their rooms with a sea-view – have since entered into a long and painful battle for compensation from local authorities and the French State. At the time of writing, the building itself is facing the inevitable prospect of being demolished – if it doesn’t simply collapse of its own accord first.

After admiring some impressive, colourful street art that embellishes some of the ground-floor exterior walls, I bravely did what any self-respecting urban explorer would have done in my situation, and trespassed just enough to see inside what remains of the building. It was a haunting and harrowing feeling to be taking in the interior of le Signal, with graffiti on the walls, old radiators strewn on the ground, doors, cupboards and wardrobes all wide open, and bits of broken glass scattered everywhere. Being in somebody’s apartment naturally felt wrong, but it also put this grand urban planning misdemeanour into perspective: the view over the Atlantic Ocean which some had put their life savings into making their own was now framed by empty window frames and a desperate sense of loss. Whatever came next on our cycle tour was bound to seem trivial by comparison.

And what came next involved about stocking up on food to make it in one piece through the next stretch of our ride, taking us into the central section of the Médoc presqû’île along quiet roads through wide expanses of marshland and deserted villages with little or no dining options. We eventually dug into our picnic lunch in the shade of trees on the town square in Saint-Vivien-de-Médoc, where the church is a curious hotchpotch of architectural styles: its apse dates all the way back to the 12th century, while other sections were gradually added over time, culminating in the addition of a bell tower in 1875, which was destroyed by bombs during the Second World War. A new bell tower was erected in 1957.

We eased our way back to the estuary coastline and we reached Jau-Dignac-et-Loirac where we visited the immensely photogenic Phare de Richard lighthouse, which was recently granted its own standalone article on the blog. The lighthouse was first built in 1843, at a spot on the bank of the estuary where a tall poplar tree, known as “l’Arbre de Richard”, stood and served as a navigation aid for sailors until it was destroyed by a violent storm in 1830. However, after entering into service, it was soon established that the Phare de Richard had one serious shortcoming: at just 18 metres, it was too small! And so, in 1870, navigation duties were handed over to a less elaborate but taller (31 metres) and more effective metallic structure, and the two lighthouses cohabited side by side for nearly 80 years.

But by the 1950s, shipping navigation methods had evolved on the estuary, switching to the use of beacons or buoys. The second, taller lighthouse therefore ceased operations in 1953 and was demolished three years later to be used for scrap. The surviving older, shorter Phare de Richard, along with the surrounding land were sold on to private owners, who subsequently abandoned the lighthouse, which fell into a serious state of disrepair.

That was the case until the 1980s, when a group of local youths took it upon themselves to clean up the site, out of a combination of boredom and frustration when they saw the state of neglect the original lighthouse was now in. In their endeavour they soon gained the support of the local mayor and council, and come 1988 the land was re-acquired by the municipality. Over the following years, the lighthouse was restored from bottom to top, and in 1993 a non-profit association was set up to bring the lighthouse back to life as a heritage site, to draw tourists and organize cultural activities.

For a token admission fee (two euros) we climbed the 63 steps to the top of the structure and, from a small platform that stretches around the top of the circular building, enjoyed the unique vantage point over the estuary, the view stretching as far as Talmont-sur-Gironde, where we had been barely 24 hours earlier.

Back in the saddles we set off towards the south, making a short impromptu stop before we’d even left Jau-Dignac-et-Loirac to view the so-called Site de la Chapelle, a small plot of land which proved to be of historical and archaeological interest when the remains of a Gallo-Roman period temple were uncovered during routine farming operations in 2000. Further finds showed that a burial church and cemetery were established on the site in medieval times. The bottom line is that there’s not much to see there, but the local council has ploughed a lot of resources into building a raised viewing platform, producing a whole series of extremely detailed information panels, and installing low-height blocks and columns indicating where the buildings stood in the past.

From here on, the Médoc’s famous vineyards began in earnest as we descended as far as Saint-Seurin-de-Cadourne, a small community to the north of Pauillac and Saint-Estèphe. Our rooms for the night were in a bed and breakfast in a converted barn that had, in the past, served as a makeshift drama school and theatre for locals. We were directed to the only nearby restaurant, whose chef, Gabriel Gette, most certainly deserves a namecheck here because his immensely creative and imaginative cuisine was of such a high calibre that he is most definitely going places. There could not have been a better way to wrap up day three.

|

| Gironde estuary cycle tour day 3 mapped out. |

0 commentaires: