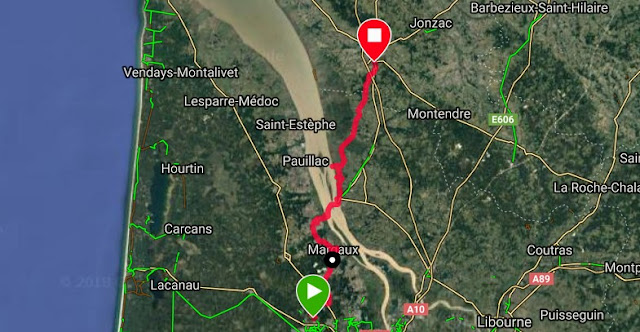

A few weeks back my wife Muriel, my father-in-law Michel and I hopped onto our respective bikes with the sole aim of departing from Saint-Aubin-de-Médoc, cycling up the right bank of the Gironde estuary as far as Royan, and then returning to base back down the left bank. We were all set for four full days and 285 kilometres of cycling. And this is how it went!

Immediately heading north, the suburban landscape north of Bordeaux segued with ease into the rolling, sprawling plains of the Médoc winegrowing territory and we were soon admiring several of the area’s most renowned châteaux. Some, such as Château Sénéjac, seemed to be the archetypal mansion house and grounds. Others were more surprising. Take Château d’Arsac, where the owner has positioned extravagant and outsize works of modern art in amongst the vines, and the unconventional shoebox-like Château Tour de Besson. Then there’s the sheer scale of the spectacular Château Cantenac-Brown which we stopped to admire just short of hitting the legendary village of Margaux, where we alighted for photos and pleasantries in front of the mythical Château Margaux, before viewing its brand new winery building.

|

| Modern art in the grounds of Château d'Arsac. |

|

| Cycling up to Château Margaux. |

We continued to make steady headway northwards to Lamarque and had a little time to kill before reaching the ferry port proper, where we were due to catch a ferry ‘cross the Gironde. We viewed a restored windmill (moulin de Malescasse), cycled past the tall steeple of Saint-Seurin church topped off by its unusual panoramic viewing platform, and made a short detour to explore a curious ghost railway station.

The story goes that in the latter years of the 19th century, plans were drawn up for a railway line to connect nearby Moulis (and the established Bordeaux-Le Verdon line) with the port in Lamarque, to facilitate the transport of goods to the water’s edge. Much of the infrastructure was built in the mid-1880s to accommodate the line, including level crossings and stops in Cussac and Lamarque. But, for “administrative reasons” (according to the information panel which retraces the story), the plans were scrapped 20 years later, the tracks were never laid and the rail link was never to be.

|

| Lamarque's ghost railway station. |

The estuary-side building we visited was therefore what should have become the “gare maritime” and was to serve as the link between rail and water. Today, the two-storey building lies virtually in ruins although it possibly serves as a makeshift workshop and meeting point for fisherfolk who spend their days on the nearby "carrelet" fishing huts, wooden fishing huts which have been built on stilts and which are very much characteristic of the Gironde estuary waterfront. Their main implement is a square-shaped pulley-operated net (or “filet carré”) which has given the humble shacks their name.

We finally made it to the port and embarked on the Sébastien-Vauban ferry which connects Lamarque and Blaye, a State-run service which has been operational since 1934. This latest boat entered service in 2014 and its name is an apt reference to the 17th-century military architect and engineer who dreamt up the fortifications built either side of the estuary as well as on an island, that combined to form the so-called “verrou de l’Estuaire” (the bolt of the Gironde estuary) to protect the area from foreign invaders. On the left bank, this took the shape of the extensive Fort Médoc. Mid-estuary a more minimalist structure was built on Île-Pâté. Meanwhile, we were about to alight in Blaye, a mid-sized town which is arguably best-known for its large-scale citadel.

|

| The ferry that connects Lamarque and Blaye. |

It was market day down by the waterfront in Blaye, making for far too many food options for three hungry cyclists, although we did eventually manage to narrow things down to three radically different combinations of takeaway dishes and desserts. From there we trekked up to the citadel, the tall stone walls of which encase what is almost a self-contained village in its own right, encompassing pre-existing edifices including the 12th-century Château des Rudel, the 13th-century Porte de Liverneuf and the 15th-century Tour de l’Eguilette. We followed the course of the perimeter walls, taking in the view over the estuary, uncovering a tiny vineyard and even entering the municipal campsite, which must be an oddball spot to pitch a tent for a night or two.

|

| A campsite plot within the perimeter walls of Blaye citadel! |

That, however, was not our plan as we still had a full afternoon of cycling ahead of us. We progressed north of Blaye, taking in notable winegrowing establishments such as Château Segonzac, whose substantial water tower wouldn’t look out of place in New York. And, as we gradually moved inland, we made a point of making a couple of diversions to see a couple of tiny ports – Port de Bernu and Port de la Belle-Étoile – which are basically rudimentary outlets onto the estuary, each with a handful of boats tied up.

|

| Port de Bernu. |

The landscape was changing, the vineyards mixing and matching with crops of rapeseed and the occasional roaming animal; we spotted herons, snakes, sheep and even a few cows just as, in the distance, the distinctive shape of the Blayais nuclear power station drew into view. We entered the neighbouring town, Braud-et-Saint-Louis, welcomed by advertisements announcing upcoming asparagus-themed festivities (Fête de l’Asperge du Blayais) in nearby Étauliers, and the heart-warming sight of one of Gironde’s two surviving Tournesol swimming pools.

These sunflower-shaped prefabricated structures mushroomed throughout France during the 1970s and early 1980s as part of a nationwide plan known as “1000 piscines” (1,000 swimming pools) aimed at making swimming accessible to the masses. The target figure of 1,000 ultimately proved to be overly ambitious, but between 600 and 700 establishments did come to be built. Various designs were rolled out, with poetic names such as “Plein-Ciel”, “Plein-Soleil” and “Caneton”, but the most distinctive and memorable was surely the UFO-like polyester “Tournesol”, the dome of which comprised sections that were mobile, running on a rail system and making it possible to open the roof 60° either way. This resulted in the Tournesol’s most notable feature: the ability to be instantly transformed, whenever the weather permitted it, from an indoor pool into an outdoor pool.

Of France’s 183 Tournesol pools, four were located throughout Gironde. The ones built in Lesparre-Médoc and Saint-Médard-en-Jalles have been demolished, while the Braud-et-Saint-Louis and Cestas pools survive to date, and long may they continue to welcome bathers to their eminently affordable prefab facilities.

From there we continued to press still further inland, passing under the A10 motorway and entering the département of Charente-Maritime. The flat terrain had suddenly become far hillier, making for a steady freewheeling downhill section followed by a painfully steep uphill section that took us into our first port of call, Mirambeau, the sort of small French town where most commercial activity has been shifted out of the centre to identikit business units that lie on the outskirts. Mirambeau boasts two landmark châteaux, one of which (Château de Mirambeau) proved to be out of sight and the other (Château Cotard) out of bounds. We instead opted to make do with a quiet meal in our hotel and settled down for the night.

|

| Gironde Estuary cycle tour day 1 mapped out. |

0 commentaires: