An interesting post recently published on social media included a 1970s clip of a hovercraft criss-crossing the Gironde estuary between Lamarque and Blaye, on the route that is more naturally associated with its small-scale car ferries. This was news to me, and investigating further also enabled me to uncover the significant link between hovercraft and the town of Pauillac. How was this all connected, and where shall we begin?

The natural starting point is the story of one of France’s most emblematic innovators, Jean Bertin (1917-75). Among other breakthroughs, Bertin invented the technique of thrust reversal used by many jet aircraft to slow down upon landing. He was also the man behind the famous failed experimental “Aérotrain” hovertrain concept developed between 1965 and 1977 (which at the time lost out to the TGV high-speed train concept, but is not dissimilar to the hyperloop projects that are currently taking shape).

Jean Bertin (photo source: Aéroclub Jean Bertin) and his famous failed Aerotrain project. And a combine harvester.

As early as 1955, Bertin founded his own company, Bertin et Cie, and in time created dedicated subsidiaries for his various ventures. He set up one for the Aérotrain project and, in 1965, he formed SEDAM (Société d'Etude et de Développement des Aéroglisseurs Marins), operating out of Marignane, near Marseille, with a manufacturing facility close to Bayonne. SEDAM was similarly driven by air cushion technology, and was specifically focused on the development and production of what would become its “Naviplane” range of amphibious hovercraft.

SEDAM’s first key deliverable was the N300 30-ton hovercraft. Two units were produced, the Baie des Anges, configured to transport cargo, in 1967, with the Croisette coming the following year and designed to carry up to 90 passengers. Both entered into service on the Mediterranean coast, shuttling between Nice airport, Cannes, Saint-Tropez, Monaco and San-Remo in Italy. SEDAM also produced a much smaller model, the N102, designed to carry two crew and 12 passengers. It never achieved any significant success, despite extensive commercial trials in different situations such as in the Mediterranean resort of La Grande Motte, as a means of reaching isolated beaches.

An N300 in Nice (photo source: Reddit) and an N102 somewhere near La Grande Motte (photo source: Le Maxi-Mottain).

And the story goes that in 1971, the

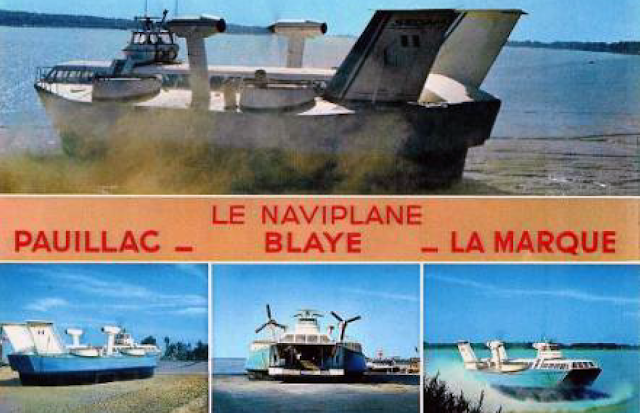

Baie des Anges N300 was acquired by the Gironde département and converted in order to be used in conjunction with the existing ferry for the regular Gironde estuary crossing between Blaye and Lamarque, as well as heading to Pauillac and sometimes Bordeaux (to a hoverport reportedly located just by Pont d’Aquitaine). It could carry four vehicles and 38 passengers and it took the hovercraft just five minutes to get from one bank to the other on its primary route. As such it functioned between July 1971 and December 1975, totting up 20,000 crossings and 4,000 operating hours.

Why did the council revert back to a more orthodox 100% ferry service? This is unclear, although three factors could easily be pinpointed. Firstly, the high levels of noise whenever the Naviplane arrived and departed, particularly in the densely-populated town of Blaye, was undoubtedly unpopular with residents. Secondly, the ferry alternative boasted a far greater capacity, able to carry 40 vehicles and 350 passengers. And thirdly, the Baie des Anges became synonymous with a couple of unfortunate incidents. In one, the Naviplane’s front door had not been securely closed and, upon discovering this, the fast-moving craft was brought to a sudden halt by the pilot. The door opened, water flowed in and a luxury Citroën ended up in the estuary. Happily, nobody was hurt. The other, during a night-time crossing, saw the hovercraft colliding with a stationary radar mast approaching Lamarque, causing structural damage to the craft.

Souvenir postcard (source: Aeromed).

This is where the hovercraft landing platform was in Lamarque. It is now home to "La Paillote de Steph".

According to some reports, this would appear to be the approximate location towards the base of Pont d'Aquitaine suspension bridge where hovercraft would land in Bordeaux.

Meanwhile, come 1973, SEDAM was struggling to make ends meet but began working on a far more substantial, 260-ton model, the N500, the largest passenger hovercraft of its time, and which was designed to carry up to 400 people, 55 cars and five coaches at speeds of up to 70 knots (around 130 kilometres per hour). Two firm orders were secured for this more ambitious project, from the Gironde département (with a view to the craft operating the Royan-Le Verdon crossing at the mouth of the Gironde estuary), and the SNCF (to be deployed on its English Channel route). There were further commercial leads from elsewhere, such as Canada, and for the route between Nice and Corsica.

Possibly drawn to the invigorating air of the Gironde estuary, in December 1975, SEDAM relocated to Pauillac, operating from a large estuary-side warehouse just to the north of the town. And Pauillac was therefore where work on the N500 commenced, conducted by one Paul Guienne, who had also directed studies on the Aérotrain project. SEDAM began building the two inaugural Naviplanes: N500-1, for the Gironde order, became known as Côte d’Argent, while the SNCF’s N500-2 was originally to be called Côte d’Opale but was subsequently given the name Ingénieur Jean Bertin as a homage to Bertin, who passed away during that period. But it would not be plain sailing for the two N500s…

The Côte d’Argent’s successful maiden flight took place on the estuary in April 1977, but during minor repair work (ahead of a ministerial visit) being carried out by SEDAM subcontractors the following month, a technician stepped onto a bare lightbulb, which exploded and set alight a spilt bucket of adhesive solvents. The whole craft caught fire and was totally destroyed in under an hour, all this occurring just a few days before it was set to be inaugurated by Prince Charles at a lavish ceremony. This tragic end is detailed, complete with archive photos, here.

Picture showing the aftermath as released by the investigation unit, one of many photos featured on the dedicated Naviplane website. After

an epic voyage from Pauillac to Boulogne-sur-Mer that took 25 hours with countless refueling stops along the Atlantic and Channel coasts, the

Ingénieur Jean Bertin entered into service in 1978 with Seaspeed, the SNCF/British Rail joint venture, operating alongside two British SR.N4 “Mountbatten class” hovercraft, and enabling the Channel to be crossed in under 30 minutes (including a record-breaking 22’15” Dover-Calais crossing which was never officially registered because no adjudicators were present!).

In 1981 the

Ingénieur Jean Bertin was transferred to Hoverspeed (the result of a merger between Seaspeed and Hoverlloyd) and was widely refurbished in response to demands issued by SNCF, re-entering service for a short period in 1983 before being decommissioned then generally left to rot and be broken up in Boulogne-sur-Mer in October 1985. (More generally, Channel hovercraft services were soon to enter a downward spiral with the opening of the Channel tunnel in 1994. The last cross-Channel hovercraft was withdrawn from service in 2000.)

The Ingénieur Jean Bertin N500 arriving in Dover. Photo source: Wikipedia.

The Ingénieur Jean Bertin N500 arriving in Dover. Photo source: Wikipedia.

Back in Pauillac, SEDAM was not doing well. The Gironde

département had withdrawn its sole order, choosing instead to redirect finances to more urgent requirements (road infrastructure and schools). In addition, the SNCF would also not be providing any further custom, as they had come to regard the British SR.N4 as a superior craft. Towards the end of the 1970s, the company was taken over by the Dubigeon-Normandie shipbuilders, but folded completely in 1983, its final project no doubt being the refurbishment of an N102 which had been purchased many years previously by an Egyptian entrepreneur based in the United Arab Emirates.

Despite the company’s collapse, the Pauillac warehouse still contained the two retired N300 hovercraft and four N102s. An auction was held in May 1983 and a Bordeaux scrap metal merchant purchased the N102s. A restaurant owner acquired the

Baie des Anges with the plan of converting it into a restaurant in Pauillac but was not authorized to do so. Plans to sell it on came to nothing so the craft stayed put in the warehouse. The

Croisette was bought by a Pauillac scrap metal merchant but it too remained on site. Towards the end of 1983, both were scrapped completely and the SEDAM story came to a quiet end.

So, what remains today of the hovercraft adventures of Pauillac and SEDAM? Well, in Pauillac, the SEDAM warehouse is now used by the Baron Philippe de Rothschild wine company for storage ahead of distributing their produce worldwide. Across the road from the massive hangar and the wide space that is now a car park (where that fateful 1977 fire destroyed N500-1), a large concrete platform serves as a reminder of where the hovercraft were launched on to the estuary. The picture below was taken from that platform, looking back towards the SEDAM hangar.

Thanks to the ever brilliant IGN Remonter le Temps

website, it is possible to see how things used to be. First, here is the scene in

1976, with what appears to be two N102s stationed outside. And here is the same view in 1977... with a single N500, in all likelihood Ingénieur Jean Bertin.

Of the N102s which ended up in the hands of a Bordeaux scrap metal merchant, in recent years two were recovered from their resting place in Villenave d’Ornon by a group of enthusiasts with a view to renovating and restoring them. That adventure is lovingly detailed here and, to cut a long story short, the two wrecks have been turned into a rejuvenated N102 Naviplane which now sits proudly on permanent display outside the Château de Savigny-lès-Beaune in the Burgundy region of France, as this Google satellite view of the area below right clearly shows!

Finally, while the use of hovercraft to transport large numbers of passengers has faded over the years (although services do still operate on routes such as that connecting Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight), the technology continues to prove its worth in complex military situations or to deal with rough terrain where no other type of craft is capable of operating. And, who knows, it may one day make a comeback, including in Gironde where the subject often comes up as a potentially effective solution to connect central Bordeaux with Blaye and the tip of the estuary!

In the meantime, interest in hovercraft has anything but waned. There are many archive clips available on Youtube, there is a fantastic website dedicated to Naviplanes alone, and in this social media age you can even find a Facebook page that talks about nothing other than the Jean Bertin N500 Naviplane!

So get googling, check out naviplane.free.fr and investigate for yourself the weird and wonderful world of hovercraft, the then-futuristic whirr of which was, for a few years in the 1970s, a common sound on the banks of the Gironde estuary!

> Find it on the Invisible Bordeaux map: Former SEDAM hovercraft factory, Pauillac; Bac Lamarque-Blaye ferry port, Lamarque; Bac Blaye-Lamarque ferry port, Blaye.

> Much of the information in this piece was found on the incredible naviplane.free.fr website, which is heavily recommended reading!

> Top photo source: Aeromed

> Cet article est également disponible en français !

0 commentaires: